Amal Al-Salamat: Living in the camp is the most painful experience

- updated: September 17, 2021

- |

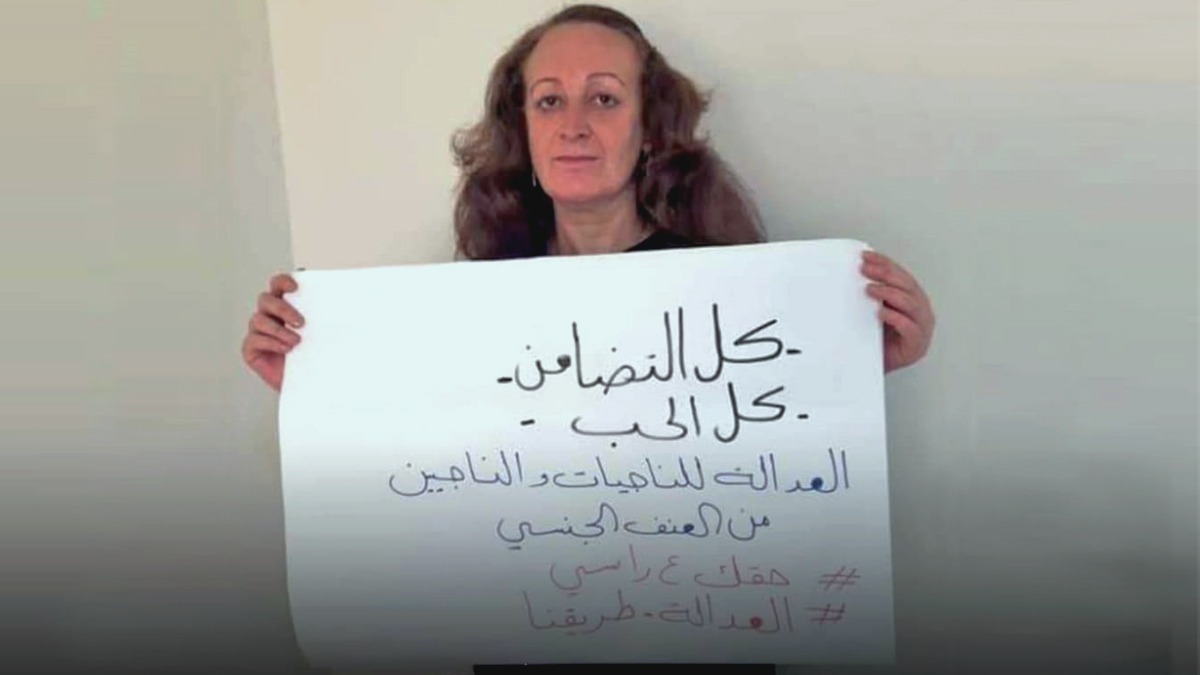

Born in Damascus, Amal Al-Salamat holds a Bachelor’s degree in Sociology from Damascus University. She was internally displaced several times before moving to Turkey where she currently lives. For seven years, she worked as a social adviser in secondary schools. Amal considers this job her greatest career achievement as it allowed her to be in direct contact with the youth. The nature of her work enabled her to create strong communication channels with this age group, and help re-shape their views on life, themselves, and their roles in society.

It was in Damascus that Amal’s memories were formed. “I lived in the poor neighborhoods of Damascus,” she says. “And the city’s historic quarters, like Bab Tuma and the Old City, were home to my memories. I have a great longing to these places whenever my soul feels the need to find love, joy and hope. At the start of the 2011 Revolution, Damascus represented a source of hope as Syrians looked up to the capital to be the spark of the Revolution.”

“I believe in revolutions, and in order for revolutions to succeed, the personal should become part of the public forming a united whole moving towards the same goals and demands, which are in our case: justice, equal citizenship, and the rule of law.’’

Amal talks at length about her enthusiasm for revolution and her participation in it like any other Syrian person dreaming of a free, democratic country under the rule of law. The start of the popular uprising created the hope of achieving this dream. “There is one scene which I wish to see happen in my country, and I believe that it sums up the country I am hoping for,” Amal says. “The scene consists of men and women, political parties and social groups all competing democratically and transparently to reach the highest office in the land.”

“The peaceful popular protests at the start of the Revolution tempted me to take part. I joined the ranks of my compatriots who took to the streets to say ‘No’ to oppression and the silencing of dissent. I had several motives to join the peaceful protests, some of which were personal while others related to the public good. I believe in revolutions, and in order for revolutions to succeed, the personal should become part of the public forming a united whole moving towards the same goals and demands, which are in our case: justice, equal citizenship, and the rule of law. I know that Syria was ruled by a totalitarian tyrannical regime where security and intelligence forces controlled every aspect of people’s lives. It was a country where no sense of equal citizenship, justice or democracy existed. Yet, it has to be said that I never wished, not for one second, for the peaceful protests to turn into an armed conflict and a bloody war.”

About her interest in political issues in Syria before the Revolution, Amal has the following to say, “I was not directly involved in any political activity before 2011, but I knew and I dreamed that change would come one day.” Amal adds, “it can be said that my interest in politics does not go back a long way but the Revolution helped bring about my political maturity. It made me appreciate the importance of political activism in the making of countries and nations, and in the development of societies and peoples. I also believe that my education helped me apply what I learned on the ground. I consider myself to be very lucky, having been born in an open-minded environment. My family was one of those families that gave women all their rights. My family had a secular tendency as well. This helped me become an independent woman with a personality of my own. However, this was limited to my immediate family because the wider community still labored under the burdens of traditions and religious misconceptions, and women enjoyed no rights whatsoever. Therefore, as soon as the popular uprising started, I focused on empowering women and advocating for their rights and causes. I was of the opinion that the Revolution should not stop at bringing down the oppressive regime, but that it should destabilize unjust traditions and the patriarchal society.”

During her numerous displacement journeys between different regions inside Syria, Amal was witness to many painful memories. “The most horrific scenes I have seen were the camps which were full of displaced people. I lived in a camp for twenty days, and I know how traumatizing this experience can be. One thing I can never forget was that I had to stand in a very long queue for about an hour in order to be able to access the toilet. Many times, I had to relieve myself behind the trees which were a bit far from the camp.” In Turkey, Amal still feels flustered and suffers from lack of stability. She faces many obstacles including linguistic challenges, finding a job and making a living, all of which make integrating into the new society even harder.

Regarding the challenges facing political activism in Syria before 2011, even if different from now, Amal says, “This is a very difficult question, because it is unfair to say that Syria had no political activism before the Revolution. There were indeed a number of parties, prisoners of conscience, political activists and political movements. All of these were violently suppressed between the 1970s and 1990s. At the same time, it can be said that the same period, until the beginning of the 21st century, had no organized political activism with a mass and popular base. This was the main problem. Most political movements or organizations were limited to the cultural elite. The majority of the Syrian people were farmers, state employees, or small earners. These people were forced to submit their wills to the one-party ‘the Ba’ath Party’. In addition, the regime was pushing conspiracy theories and popularizing the idea of ‘the axis of resistance’ to paint the picture that Syria was in a state of permanent war. As a result, the majority of the people were in a state of tension, feeling that they should always be on the alert.”

The greatest challenge, Amal notes, was the heavy-handed involvement of security forces into political life, which the regime adopted publicly. As a result, members of the society preferred to stay away from politics. “The current challenges, in my opinion, are even greater,” Amal continues. “In addition to the ones I already mentioned, the Syrian society has been divided both horizontally and vertically. Several regional forces have become invested in Syria in order to impose their political agendas. There are new challenges arising from displacement and the refugee crisis. There are around 13 million Syrians who have been internally or externally displaced. This reality will create even deeper divisions and more eschewing of political activism. In addition, the intervention of extremist groups and sectarian militias breeds its own problems which will impact negatively on the future of any civil or political activity. The rapid increase in poverty and violence is also a source of major concern.”

“I was of the opinion that the Revolution should not stop at bringing down the oppressive regime, but that it should destabilize unjust traditions and the patriarchal society.”

With regard to the challenges that women in particular face, Amal says, “The challenges are varied and complex. They existed before the Revolution and only worsened afterwards. Before the Revolution, women working in the politics were often directly or indirectly affiliated with the ruling party. In other words, they were implementing the agenda set for anyone who worked in politics in Syria. In general, the laws (personal status, penal code, etc.) were not in the interest of women. Syrian women were like other women in developing countries, pigeonholed into a functional role created for them by the prevailing culture, namely their sexual function, or anything connected to their primary function in childbearing. In my opinion, after the Revolution, there was a greater opportunity for Syrian women to be involved in political work. There were many attempts to place women in positions of political decision-making, but these attempts are still insufficient compared with women’s abilities. Activating the role of women in political life still needs more work. All efforts, locally and internationally, should be concerted so that women have a fundamental role and an equal participation.”

Amal joined the SWPM in 2019. About her reasons for joining, she says, “The existence of a women’s organization was my primary motivation to join the movement, in addition to the presence of famous female activists in the movement who, in my view, have become leaders and have made great achievements at the level of the Syrian political activism. I have always believed in organized work and the importance of women’s movements, because this helps achieve my aspirations and the aspirations of many women who dream of equality. This kind of collective work will definitely bear fruit, albeit in the long run.

“The movement has actually achieved a lot on the political level,” Amal continues. “It is strongly present, through its members, in the constitutional committees and in the Syrian political organizations taking part in the political solution in Syria. The movement supports the political participation of women, as it includes all groups of women of all ages, from all nationalist and ethnic affiliations. The SWPM goes to great lengths to involve women inside Syria, which is very important. On the other hand, there are some obstacles facing the SWPM’s work. In brief, they are: material obstacles, self-regulatory obstacles related to movement itself, external obstacles related to creating a common language and a shared vision among the movement’s members who have different backgrounds, aspirations and approaches to the Syrian crisis. There are also obstacles imposed by distance, geographical dispersion, and the different spatial and temporal conditions of the members of the movement.”

“The homeland, in my view, is the place to which I have a feeling of belonging. It is the place where I do not fear expressing my opinion, or exercising my religious rituals. It is the place whose flag is the only thing that I hold dear and fight for; the place with which I have a voluntary, rather than compulsory, relationship. Finally, it is the place where I feel safe, settled, and content.”

We asked Amal about the best way to re-calibrate the compass of Syrian women and men with regards to revolutionary work. “We have not lost our sense of direction,” she answered. “The Revolution has not ended yet. We are still in a constant struggle and in a state of movement. There is nothing absolute in life and nothing is fixed from my point of view. Each period of the Revolution has its own special conditions and starting points. I think that this is not a bad thing at all, as long as we keep on learning and developing in every stage so that our vision becomes wider and our goals become clearer. I believe in the importance of the demands of the Revolution. On the personal level, my motivation to continue and adhere to the principles of the Revolution is the homeland first, the homeland second, and the homeland last. My experience of being a refugee has taught me that the place where the identity of the individual is clear, and where one can move freely is the place where you should belong and give your best efforts.”

Despite causing harrowing experiences such as bombing, displacement, and separation from family and loved ones, the past ten years have had a silver lining for Amal. “I have acquired skills that I never expected to possess,” she says. “I have worked in several leading positions in civil society organizations. I learned how to write about the concerns of the common people and their suffering. Thus, I became a journalist, and I formed a large network of relations with many Syrians from various backgrounds. It became my passion to work on making Syria a place of equal citizenship. I believe that these are some of the most positive achievements that I have made during the past years.”

Amal describes the Syria of her dreams as a country of equal citizenship, justice, rule of law, and a lot of dignity. “The homeland, in my view, is the place to which I have a feeling of belonging,” she adds. “It is the place where I do not fear expressing my opinion, or exercising my religious rituals. It is the place whose flag is the only thing that I hold dear and fight for; the place with which I have a voluntary, rather than compulsory, relationship. Finally, it is the place where I feel safe, settled, and content.”