Hiam Haj Ali, My Soul Still Lingers in Aleppo

- updated: November 5, 2020

- |

Hiam Haj Ali

“My Soul Still Lingers in Aleppo”

Hiam Haj Ali was born in Aleppo where she studied French

Literature at Aleppo University. Having only finished two years of the

four-year degree, she had to stop her studies in the wake of the Syrian

Revolution in 2011. Along with some university friends, she worked as a teacher

for two years before she started working in civil society organizations. In

2016, she was forcibly displaced from Aleppo.

“I was born and bred in Aleppo. I spent my childhood, teens

and part of my youth there. I have left

but my soul still lingers in Aleppo,” she says about her relationship with the

city.

When the 2011 uprising started, Hiam was still a secondary

school student. “Grown-ups used to treat us like we did not understand the

meaning of a revolution. On the contrary, I was personally fully aware of the

meaning of standing up against the government. I saw the terror in the eyes of

Syrians when they talked about the Assad regime. I rejected the word ‘crisis’

used by other students, usually daughters of high-ranking officials, to

describe what was happening,” she says. “Students of less-advantaged

backgrounds like us witnessed firsthand the oppression of the regime. For us, the

revolution was a promise of freedom”.

Asked about her personal motives for joining the uprising,

Hiam says, “Living in a conservative society, women’s participation in the

protests was not easy in the early days. So I tried to make a contribution away

from demonstrations and in my own way, by teaching and volunteering. As time

went by, however, the idea of the female revolutionary became more acceptable

and even welcome. This is just one positive outcome of the Syrian people’s

revolution for dignity.”

Being forcibly displaced from the city of Aleppo to the

surrounding countryside caused a psychological scar for Hiam. “Although

shelling and the siege were escalating, we always hoped for the siege to be

lifted, which happened once before. We dreamed of returning to our normal daily

routines but we never expected to be evacuated in such a hurried way,” she

says. “The noise of shooting was getting ever closer and the neighborhood was

being shelled incessantly. I was forced to pick my baby daughter and flee,

looking back in horror. Our escape from certain death was filled with fear and

a feeling of helplessness. I still can’t believe that at some points we had to

walk over another person’s dead body to continue our way. How did we even

manage to escape?”

Her “journey of death” led her to the town of Azaz, where

she had to start her life from scratch. “I sought the help of my friends and

relatives as well as my husband, in order to regain my balance and start anew.

Then I started looking for a job. It was around that time that the city of

al-Bab was liberated. I decided to move there because it was a similar

environment to Aleppo and I would find it easier to settle there. And so, I started

a new chapter of my life in al-Bab. I finished my university degree, graduated

and had my second child.”

“I have always had questions about how marginalized we were

as a people. So I started to participate in events related to the political

solution in Syria. I became convinced that I must not allow anyone else to

speak on my behalf because I can make my voice heard.”

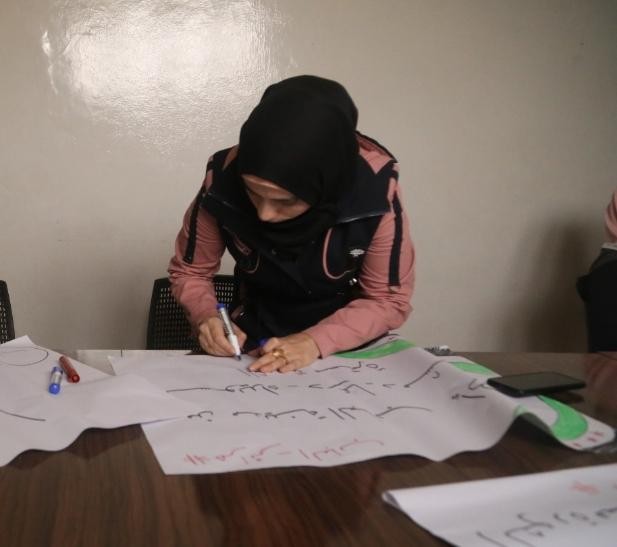

Talking about her interest in political activism, Hiam says,

“Women are politically marginalized in our society. Until recently, even

working on building women’s capacities and empowering their political

involvement was unheard of. As for me, it all started in 2018 when a conference

was organized for women living in the northern and eastern countryside of

Aleppo and Idlib. I attended the conference and I started to learn concepts

that were new to me like women’s empowerment and political involvement.” The

conference, Hiam says, had a hostile reception locally due to misconceptions

about women’s role in society. Many believed that “a woman’s place is her home;

the only role she has is indoors.” Meanwhile, Hiam started working with several

organizations doing field research. One organization manager offered her a

volunteering position on their team in al-Bab, working on training and women’s empowerment.

It was in this organization that Hiam had her first election experience. As she

witnessed male and female members nominate themselves, she says that she “began

to understand how marginalized we were as a people.” This made her more keen on

participating in events related to the political solution in Syria. “I became

convinced that I must not allow anyone else to speak on my behalf because I can

make my voice heard.”

About the challenges facing political activism in Syria,

Hiam says, “the lack of trust between people and politicians makes it difficult

for those who have an interest in politics to start a career in this field. The

Syrian people’s life under an authoritarian regime and a single ruling party

was so traumatic that the very concept of politics became associated in their

minds with deeply-rooted skepticism.

One of the greatest difficulties facing Syrian women in

politics, Hiam adds, is the stereotypical view which limits their potential. Until

very recently, it was socially-unacceptable for a woman to express her

political views or show an interest in studying something like political

science. “It can’t be denied that some women bought into this stereotype and behaved

in the same way they were expected to behave,” Haim noted.

“Women are genuinely equal to men. We can dream

big and we can work to achieve our dreams. Pay no attention to the obstacles

because one day they will become your motivation. War, displacement, looking

after children, growing old, all these factor must not stop you from realizing

your dreams.”

Joining the Syrian Women’s Political Movement (SWPM) was an

easy decision. “I heard about the movement and its activities. It combined two

important elements for me: politics and female activism. So I applied to join

as soon as I could.”

“The SWPM helped me to know more about politics and the

world from a woman’s point of view. Many of the members were politicians and

activists who had great experience in their fields. Some were even members of the

Syrian Constitutional Committee,” she adds. “It was essential, therefore, to

have an organization such as SWPM that connects us together so that we can

network and coordinate our efforts, especially on vital issues such as the question

of detainees because this is something that is highly important for people

inside Syria.”

Hiam believes that Syrians today need to rethink their

priorities. “The famous slogan that demanded the fall of the regime back in

2011 has to change because the circumstances have changed. The parties of the

conflict are no longer the regime and the opposition. Rather, the Syrian war

has become an international battleground for multiple international players.

Today, it does not suffice to say the head of the regime, Bashar al-Assad, has

to resign. We need to demand accountability and transitional justice,” she

says.

Her sense of responsibility towards her daughter and son

urges her to continue her political and feminist struggle. “My generation blames

the previous generations for succumbing to the regime’s oppression. By the same

token, we must not be silent; we must not back away from our revolution; and we

must not allow this regime to stay in power,” she says.

The past few years held some really trying times for Hiam. “My

injury during the shelling, the destruction of our house, watching my mother’s

face silently observing all this cruelty, the death of my sister’s three

children, these were some of the events that impacted me deeply.”

Still, these difficult years held some highlights for Hiam.

As she told us the story of her injury, she comments, “I was taken to Turkey

for treatment. I was worried that I would not be able to return. But love was

stronger than war. Love made me return to my city Aleppo and when I arrived I

felt that I was born again. The dreams of the revolution and freedom started to

grow again inside me.” Another fond memory she holds is when her two-and-a-half-year

old daughter asked her about a flag of the revolution which she was carrying.

“‘What is that?’ she asked. ‘Revolution,’ I answered. She was such a young

girl,” Hiam says, “but she appreciated the sentiments behind the flag unlike

many adults who still do not comprehend what the revolution really means.”

For the Syrian women, Hiam has a piece of advice. “Women are

genuinely equal to men. We can dream big and we can work to achieve our dreams.

Pay no attention to the obstacles because one day they will become your

motivation. War, displacement, looking after children, growing old, all these

factor must not stop you from realizing your dreams.”

Hiam says: “I have many dreams for Syria. I always think of

my seventy-year-old mother and how she lived her life under tyranny. I want my

life to be a normal life, in a country where my dignity and my freedom are protected,

a place where I can express my political views and practice my social life

without pressure. I dream also that Syrian men and women can live together

without thinking about sectarian divisions, religious privileges, regionalism,

or marginalization.”