“Wave”, an art exhibition, and a political vision

- updated: December 28, 2022

- |

Interview with the Curator and the Executive Director of the Syrian Women’s Political Movement Alma Salem

Interviewed by Raja Salim

Wave Exhibition

Wave: noun [C], plural: waves. In physics, a wave is a form of energy transfer. Waves are distinguished from particles by having a set of physical behaviors, including propagation, reflection, refraction, interference, intersection, diffraction, scattering, dispersing. Its properties also differ between material and immaterial mediums, as well as its forms of movement as it may move horizontally or longitudinally. in terms of reflection, transmission, dispersion, and scattering. It can move in the form of a wavelet. Waves are also characterized by their cohesiveness as they move in the form of compressions and rarefactions in different media (solid, liquid and gas) because they do not need large cohesion forces between molecules.

The Curator and Executive Director of the Syrian Women’s Political Movement Alma Salem chose for the Fourth General Conference of the SWPM to be accompanied by “Wave” art exhibition. Ten years after the wave of Arab Spring revolutions, the exhibition examines its repercussions on the current Syrian feminist ‘wave’. It also examines the impact of the SWPM five years after its foundation in breaking the stereotypes surrounding women’s position in society, and in pushing that wave towards better presence for women in public affairs and at decision-making positions.

The word wave has been associated with feminist movements since their early emergence in the early twentieth century. When I asked you why you chose the title Wave, you started by linking your artistic approach to the physical nature of the wave. Tell me more about that.

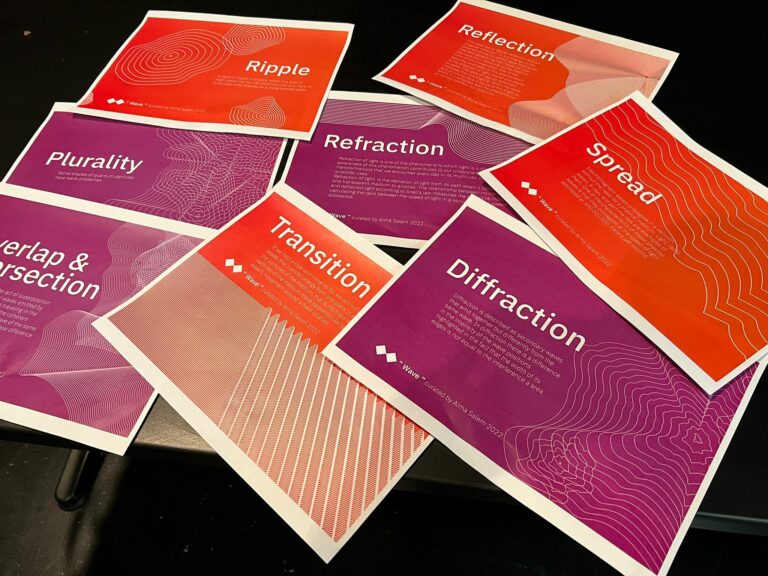

At first, we were motivated by the question: Are we currently experiencing a new Syrian feminist wave? To discuss this question, it is necessary to determine our position in relation to several key ideas, starting with the history of global feminist movements. That is why I chose to arrange the chronologically from the earliest to the most recent. As for the physics of “waves”, the exhibition depicts the manifestations of the wave, its physical behavior, and the different properties according to surrounding factors affecting it such as light, space, sound, fluids, and others. I turned towards physics as a source of poetic imagery in order to try to understand what we have experienced as Syrians over the past ten years.

These manifestations caught my attention during my research into wave physics because they intersect with our feminist movement. I invited a group of members of the movement to write texts about each of these properties which are: diffraction, refraction, interference and intersection, direction, multiplicity, reflection, transition, propagation, wavelets, scattering, and dispersion.

I was especially interested in the refraction of waves, and how you linked it to the start of the Arab Spring. Why did you choose this property to refer to the beginning of revolutions?

By definition, refraction of light is its bending from its path as it moves from one transparent medium to another transparent medium. So, instead of continuing to move along the same straight line, it bends at the point of transition between the two mediums. For me, the start of the Arab Spring was a moment of decisive change, and it changed the path that the peoples of the region were forced to follow for decades. The people took a completely different path, a path of revolution and radical change. Here I quote the opening lines from Shams Antar’s article ‘Revolutionary Feminism and the Arab Spring’, where she says: “If the waves decide to sweep the beach, no force can stop them. These are the waves of feminism driven by the winds of change.”

I have always studied, experimented and researched artistic “spaces”. Today, I am working on Syria as a space or an area, based on Homi K. Bhabha’s Third Space theory, or being in more than one space at the same time. If a person in Syria is talking at this moment with a person in India, the place that really brings them together is not Syria or India, it is a virtual (new) third place free from time, place, geography, history and their dynamics. This theory emerged in media studies in the sixties, breaking the theory of the “Here and Now”, which is one of the most important theories in modern art. In my work on Syria, I try to find a conceptual creative solution to the encounter, which gives absolute freedom to the artist to implement their ideas without restrictions, and to free the artwork itself from the protocols of visiting its place of display, or the difficulty of movement of its organizers or participants. The concept of the third space allowed me to create non-physical artworks, downloadable and accessible to exhibitions at the click of a button. My goal in all the spaces that I have created, and I am working to create, is to make the artistic product reach as many people as possible and allow them to interact with it according to their circumstances. The Wave exhibition offers the framework for responding to the needs of members through programs and projects that provide them with direct means of collecting texts as we work together to create creative content such as videos, essays, etc. Fifty-one members were invited to participate either with a selfie, a clip from a song they love, a place that means something to them, or a moment they remember. We designed the entire exhibition with each member having their own space within a teamwork environment.

The Wave exhibition has three sections: ‘Their Messages’, ‘Their Moments’, and ‘Their Faces’. Everyone who attended the exhibition sensed a peculiarity that focused on the members of the movement not as a single bloc representing a political body, but as individuals. It is as if you wanted to hear the voice of each one individually, and how each of them, with her differences from the others and her intersections with them, is an essential part of the bigger picture of the SWPM, and the Syrian feminist movement in general. In making Their Faces, for example, you tried to make the visitor’s perspective focused on each member’s face. Why did you choose this approach?

As the launch of the exhibition coincided with the fifth anniversary of the founding of the SWPM, the work as a whole has the character of reflection. The aim of their faces is to celebrate female members as politicians and actors in public affairs. In our societies, a male politician is often called a ‘political face’, while women are usually called ‘ladies of society’ (socialites) or ‘social faces’. There is always a link between the face and the position, power, presence, the right to speak, the right to make decisions, the right to be present in decision-making circles and to be in the public space in general. Even the general culture does not welcome the culture of showing women’s faces and associating their names with their photos and physical presence. For example, there are several Syrian women who are active in politics, some of whom are well-known names, but how many of them can people recognize from their faces? As for male politicians, if we mention one of them, most Syrian women and men immediately remember what he looks like. Many reasons have prevented women politicians from appearing in public in the past ten years, including fear of arrest, fear of society, and fear of defamation. It is known that the political scene was incomplete in the past decades due to the absence of women. Today, with the tireless efforts of women, including members of the SWPM, to influence politically and regain our stolen space, I wanted to make this work an attempt to imprint the faces of these women in the Syrian collective memory. The credit for the design and implementation of the idea of ‘Their Faces’ should go to the artist, Hakawati, and the Warsha team, who chose to display the ‘Their Faces’ show through a kaleidoscope, which is like a telescope that contains colored scraps of different shapes and colors. Whenever it is moved, the colors and shapes change. Thus, the kaleidoscope symbolizes unlimited diversity and the element of surprise, which would motivate the viewer to wonder who this face belongs to. Who are those women? Why do we celebrate them? I am interested in promoting a culture of questioning in our society. Whether out of curiosity or for gathering information, it doesn’t matter, as long as people ask; who is that lady sitting at the negotiating table? Here, it is important to highlight the importance of the SWPM’s view of women’s role in politics. For example, when UN envoy Staffan de Mistura founded the Women’s Advisory Council in 2016, the SWPM refused to limit the role of women to an advisory role, because they believed that women should be in decision-making positions. Therefore, ‘Their Faces’ is an invitation to know and enquire about these women, about their history and how they reached where they are, their role in Syria’s present and future. Women are not only a symbolic presence or are there because of an imposed quota as some people claim. Many of these women have a long history of struggle and in politics. They have worked hard and are striving daily to make Syria a country of equal citizenship. They are out there, and we just have to get to know them.

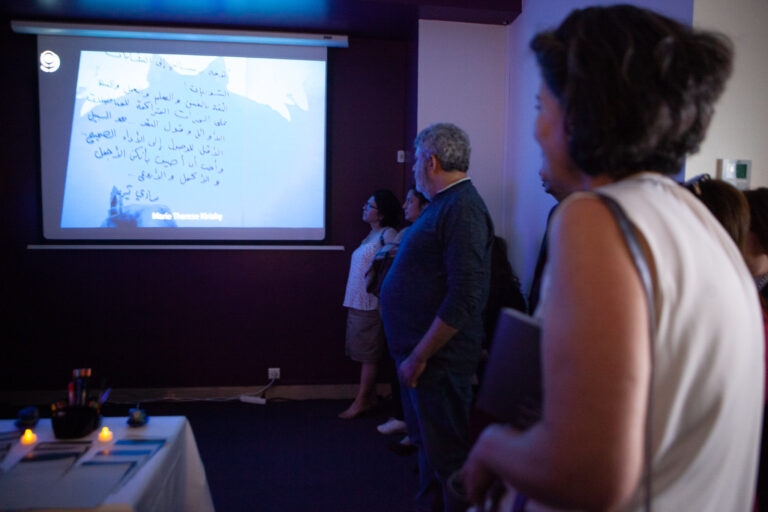

The first Wave exhibition was held in Paris and Istanbul, in July 2022. The second was in your city of residence, Montreal, in October 2022, and it only included the presentation of “Their Faces”. Y invited the attendees to interact with the show with dance or physical expression, so to speak. Your invitation received amazing interaction, whether from the audience in general, or from professional dancers from Syria, Armenia, and Iran. What did the interactive factor add to the show in Montreal?

Yes, in Montreal I made the show more intensive and wrote a text that included the content of the other two parts: Their Messages and Their Moments. I read the text as the faces of the SWPM members were shown on the screen, which turned their faces into a poetic, philosophical, and visual experience. The text contains passages about the wave and its manifestations. I tried to relate the philosophy of the wave to the faces of the members, in addition to concluding each passage about a characteristic with a question along these lines: “Did you see the light passing through your eyes?” “Did you feel our wave shaking you?” These questions invite the public to reflect on our experience and how they received this work. In Paris, the audience was made up of SWPM members. In Montreal the invitation was open to all, and the idea of intersection was present through the diversity of the audience who came from different ethnicities and nationalities. The dancers themselves included a dancer from Syria, an Armenian dancer dancing on the border with Azerbaijan, a Canadian dancer and an Iranian dancer supporting the women’s revolution in her country. The dancers improvised their movements as they listened to the text. There was no rehearsal. What I did was to share with them vocabulary and ideas related to the concept of the wave, and left them some time to think about the expression closest to each one. When the show began, the dancers, even non-dancers, began to advance to the stage and interact with their bodies with the text accompanying Their Faces. We simply wanted the expression to be spontaneous and to stem from the instantaneous interaction with sound and image. The interaction between dance, text and image, as well as between the dancers themselves, elevated the exhibition to a level of universality, not as a work of art, but as a human work that can touch anyone, anywhere in the world.

Valerie Sabbah, Dancer: The dynamics of text and image were very moving, the work as a whole stimulated my body to move.

Dena Davida, Dancer: It was as if my feelings were hypnotized. The words turned into sounds, into sound waves, into movement.

In the “Their Moments” show, artist Zoya uses Google Earth to link each member to a place that has a place in their memory or a place that witnessed a moment of change in their life. She tries then to approach this place and visit it virtually. How were these visits?

During the preparation period, and during discussions with members, they recalled places that were engraved in their memories. This created an opportunity for each one to stand with herself and reflect upon that moment of change and its impact on her personal life and career. Organizing and preparing this work, which was carried out by my colleague Mona Katoub, the SWPM’s Media Officer, was in itself an impressive and rich experience on a human level. One of the objectives of the project is also to highlight our current diaspora as members of the SWPM, and as an administrative team. We exist in 21 countries in addition to Syria of course. This in itself constitutes a strong feminist solidarity network that supports us and is spread in most continents of the world. As for the technical aspect of the project, Zoya discovered during her technical research that Google Earth cannot give as many details of places as it does in Europe or the US, where the service can reach such accuracy that you can enter a park, a school, or a street in a small residential neighborhood. However, this did not hinder the project. Rather, it became a new expression of the relationship between Google and memory and an opportunity to raise awareness that regardless of the reason behind this policy of blackout, it deprives people of forms of unimaginable benefits. As a result, this project created a map specifically made for the SWPM.

The Wave exhibition also included a virtual interactive show called “Their Messages” which aimed at creating a space for Syrian women, regardless of their geographical location, to exchange messages either during the exhibition or at any time through the movement’s website. In your opinion, what is the importance of creating this public space for sharing and expressing opinions among Syrian women, and how would you describe the reaction to it?

We created this space as an opportunity for Syrian women and men to send messages to Syrian women to express appreciation, gratitude, recognition, or thanks for initiatives and contributions. This initiative was well-received during the Paris exhibition by members of the SWPM present, as well as diplomats who also sent messages to Syrian women. Recognizing, naming and appreciating women’s efforts is important on several levels, such as giving moral support to everyone who tries to be part of the change. It is also an opportunity to introduce active and influential women, both on the Syrian scene in general and in their immediate circles. This space focuses on the word and its importance in feminist and political work. In particular, it promotes the word as a concept that constitutes an inclusive, mutual and founding discourse for a common future, and a cornerstone of change in the feminist movement. This space is still available on the movement’s website to receive and share messages.

Let’s talk about the fact that the first exhibition was directed to female members, whether in Paris, Turkey, or the interactive virtual show in Syria. You told me when we spoke during my visit to the exhibition that this exhibition is very special to you, why?

In the field of curation research and audience analysis, which is a whole field of knowledge, there are artists who believe in educating the public. I am absolutely against this trend. There are theories such as immersive experience, engaging the audience, and interaction. All of them allow the audience to be part of the work, interact with it, develop it, or take it to places that the artist did not expect. This is what happened here. We showed ‘Their Faces’ on four occasions: Istanbul, Paris, Montreal, and an online show. The difference was mainly the audience. In Paris, the show was attended by those who participated in the artwork. Even though the exhibition was open to the public, it was the presence of the members that was really important to me. The way they were affected by the work and their tears as they came out of the exhibition said a lot about what they received. Each one took a step back and took a close look at herself. She saw a celebration of her and her work. She saw recognition for her and for every step she took in her struggle. The members were the exhibition, its audience, and its message. Regarding the show in Turkey, it was not scheduled to be shown that day in Istanbul and it was decided to display it at the last minute. So, we did not have the opportunity to show it on three screens and had to make do with one screen. So perhaps the exhibition did not touch the audience with the same depth. This was evident from a questionnaire that we gave to the members as another form of audience interaction. As a curator I was at that time in Paris, and I could not be in two places at the same time. This also posed a technical question and a challenge about the importance of the presence of the curator in the exhibition. This is something that I had previously researched and am still experimenting with in my career. In Montreal, as I mentioned, the audience interacted with dance, words, and gratitude for the experience.

The conclusion is that this experience confirmed the vision that frames my artistic practice: in order for a work of art to have a political impact, it must achieve the same aesthetic standards as any work of art that does not necessarily seek social change and works within the scope of art for art’s sake. The aesthetic itself is a political tool for building freedom and peace, but it is free from politicization and propaganda.

On this topic, you can read this article by the curator.

As a curator whose work has been featured in some of the world’s most important venues, what have you experienced, in terms of artistic practice, in this exhibition that you have never experienced before?

In my previous works, including (Kashash) and Tourab (Earth), I used to create the artistic space and then I invited artists, intellectuals, and researchers to participate. Every time, we found ourselves resisting a discourse that does not conform to the values of our revolution, a discourse about naming and classifying the conflict. We encountered this a lot when dealing with the international community or the main players in the political process in Syria. There were attempts to politicize artistic spaces and turn them into media spaces at the expense of artists who are non-politicized. Even when artists take a political position, they do not adopt a discourse that serves any agenda. Rather, they present art that seeks to be universal. We faced pressure to turn Syrian art into political leverage. This has always put me as a curator in a defensive position as if I was the guardian of this space, being attacked violently and facing the attack violently. Violence has been an aspect of artistic work in the past ten years. On the contrary, today I am embraced in a political space that is in complete harmony with its vision, an entity whose values I share and defend.

It is a fact that I have tried in the past to do my best as a curator to sit at decision-making tables and I succeeded in holding exhibitions in the corridors alongside these meetings. Artistically, I was unable to have the same influence that the SWPM has as a group. Naturally, I wanted to experience a different space and to go all the way, i.e., to experience politics in their ‘brut’ format , then return from political spheres to art where I truly belong. The movement welcomed me, provided me with protection and supported me in completing an art project whose message is in harmony with its milieu. Despite my involvement in the political scene in a way that stems from my values, I still reject the politicization of art. Over the many years of my work, I have not come to terms with the politicization of art and turning it into propaganda even if it is in favor of what I personally believe in. I follow a kind of self-censorship to protect the artistic space because I am coming to the political field from an artistic background and not the other way around. Until this very day, I am the Executive Director of the SWPM, but I still consider myself as an independent curator, independent even from the political message that I campaign for. The artistic challenge I take up every morning is to master drawing these boundaries between art and politics.

In conclusion, where do you see the future direction of ‘wave’ as a work of art? Where do you see the future direction of the Syrian feminist wave of which you are a member?

‘Wave’ as an exhibition. Usually the life cycle of an exhibition is three years. It is fulfilling that many members requested for ‘Wave’ to be displayed in events in which they participate. For me, this exhibition has left my ownership and is now the property of any Syrian woman that considers herself part of this wave.

Today, I am in the process of preparing a new work, a personal project about Alma, her place within the wave and the wave’s impact on me personally. I recently finished fifty years of age. It was a pivotal year in my life on all levels: psychological, physical, emotional, and professional. The next exhibition will be about self-reflection.

As for the Syrian feminist movement, in my opinion, it has overcome its most difficult stages. It has been founded; some of its features have crystallized; it has been widely recognized; and now there is a group of supportive and collaborative networks that share at least their broad lines. The obstacles facing us today are technical problems related to strategic planning for feminist action. We also need to make sure that our efforts are in unison to make sure that we are doing our part in the right places and at the right time. Most importantly, we need to start paying attention to the Syrian feminist experience, by learning from it, taking examples from it, researching it, writing about it, discussing it, analyzing it, and listening to the various voices that make it up. In my opinion, it is time to stop importing feminist experiences from other countries and forcing them into the Syrian context. Our reality today is full of intersections, differences, consensuses and peculiar experiences. Soon after, a new generation will come with new needs and different aspirations, which must rely on local experience, either to build on it or to demolish it to reformulate its narrative. But the experience and the stages of its maturity must be documented.

Members of the SWPM who attended the opening of Wave exhibition in Paris said:

Thuraya Hijazi: ‘Wave’ exhibition represents us as human beings and the changes we are going through. It expresses all of us, especially women. I was moved by the exhibition because it touches the human condition. We all lost a person, a place or a feeling, the exhibition was an opportunity to remember.

Maryam Jalabi: I didn’t have any expectations before visiting the ‘Wave’ exhibition, but the moment I entered the showroom, I couldn’t help crying. I was very moved as I thought of us as human beings. I thought of women and their positive energies, their love of music, of places, of family, of their experiences. I communicated with the human side of the members. It is touching to know the favorite music of Sanaa Hawija, Masa Mufti, Thuraya Hijazi, or anyone else. There is a saying in Buddhism that means that as humans we are part of a running river and are in constant motion. We are part of this history which never stops.

Hiam Al-Shirout: I was touched by the ‘Wave’ exhibition. I participated with a message in the exhibition but being here and seeing the work closely was very moving. I felt that I was part of this group. I was happy that this work brought me together with members of the SWPM despite our diaspora.

Wave Exhibition Catalogue in Arabic

Wave Exhibition Catalogue in English